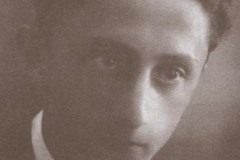

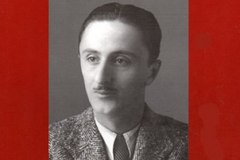

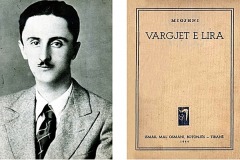

Milosh Gjergj Nikolla (1911 – 1937), Migjeni.

Born on October 13, 1911, in Shkoder, in the town of Friars, in that house in front of their church, which was demolished in 1940, in order to widen the street and the square in front of the Franciscan church. According to the house book, in which the main events of all family members are recorded (birth, death, marriage), September 30, 1911 is recorded as the date of the poet’s birth, but this is according to the old calendar style, and they changed it since the date of death as well his is according to the new style. Grandfather Nikolla Dibrani – he was called by this generic surname, because the family originated from Dibra e Madhe, from the Orthodox Albanian villages of Reka (the same province where the Albanian patriotic poet Josif Jovan Bagëri was born) – who survived the hardships of the 20th century 19th.

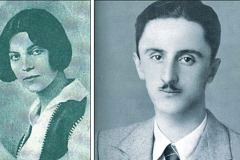

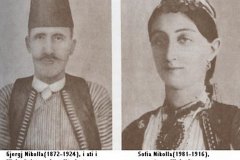

We have many families scattered in this northern city: Gjergaj, Siliqi, Banushi, Kadiqi, Dibra, and others. Nikolla Dibrani was a mason by trade, and they say that he took part in the construction of the Orthodox church in Shkoder. When he was working as a mason in different towns in Montenegro, Nikola met and married a girl from Kuçi, Stake Milani, who, like all the residents of that province, spoke Albanian as her mother tongue. When Nikola Dibrani died in Montenegro, there from the weather in 1876, he left behind two sons: Gjoken (Gjergjin) and Kristo, very young. Gjergjj Nikola became a servant of the Berovices, who used him as if they had their own son. They also helped the widowed orphan in the Italian school. Later, while keeping their accounts, he also helped them in a pub, next to their warehouse, in which he worked for his own account selling food products. Gjergji (or Gjoka) was a wise, honest and characterful man. For these qualities, for the first time they chose him epitropa in the Orthodox Church and, because they valued and honored him, his community sent him to represent in the Ecclesiastical Congress of Berat in 1922. With his good qualities, he won a life partner equipped with culture and rare beauty, Sofi Anastas Kokoshin, whom he married on September 17, 1900.

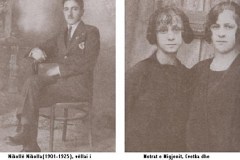

This woman was born on October 15, 1881 and died on August 16, 1916, leaving behind her husband with two sons and four daughters under the domestic care of than the old mother-in-law. Miloš was five years old then.  In 1910, Gjergji took over a grocery store, and ten years later, when his gardener Ilia Trimčev died, he took over his store, which he kept until he died, on March 21, 1924, at the age of fifty-two. In this shop I help the first child of the house, Nikolla, who was born on October 30, 1901 and died a year later from pleurisy. Devastated by these misfortunes that beset her one after the other, the brave eighty-year-old grandmother also died in 1926. Now the family was scattered. Miloš’s aunts tell how happy this family was when the parents were still alive, and with how much care and love the father raised the six children, who were left without a mother when they were babies. Especially the little Miloš, the delicate Miloš in body and feelings, he surrounded him with the biggest charms. He never put him to work, he never broke his heart, and when he called him to the store, he filled his pockets with candy and told him: “Now, go play with your friends.” The parents, who had their own school, wanted to give their children a good education, sons and daughters. Sofia, his mother, graduated from the school of Italian nuns in Shkoder; the eldest daughters were sent there in time, while the son, the eldest of the house, Nikolla, went to the Italian school for boys and finished the third grade with a score of 69 out of 70 in total, according to the notice issued by the directorate on June 13 1914. Of all the children, only the very little one, Miloš and his younger sister, Olga, went to the Serbian school as babies.

In 1910, Gjergji took over a grocery store, and ten years later, when his gardener Ilia Trimčev died, he took over his store, which he kept until he died, on March 21, 1924, at the age of fifty-two. In this shop I help the first child of the house, Nikolla, who was born on October 30, 1901 and died a year later from pleurisy. Devastated by these misfortunes that beset her one after the other, the brave eighty-year-old grandmother also died in 1926. Now the family was scattered. Miloš’s aunts tell how happy this family was when the parents were still alive, and with how much care and love the father raised the six children, who were left without a mother when they were babies. Especially the little Miloš, the delicate Miloš in body and feelings, he surrounded him with the biggest charms. He never put him to work, he never broke his heart, and when he called him to the store, he filled his pockets with candy and told him: “Now, go play with your friends.” The parents, who had their own school, wanted to give their children a good education, sons and daughters. Sofia, his mother, graduated from the school of Italian nuns in Shkoder; the eldest daughters were sent there in time, while the son, the eldest of the house, Nikolla, went to the Italian school for boys and finished the third grade with a score of 69 out of 70 in total, according to the notice issued by the directorate on June 13 1914. Of all the children, only the very little one, Miloš and his younger sister, Olga, went to the Serbian school as babies.

Miloshi, who finished the unique school in Shkoder in 1923, when his father and brother died, was in Tivar with his older sister, Lenka Jovani, married there to a mechanic from Kavaja, Llazar Jovani. Miloshi was studying in the second grade of high school when his anointed, Jovan Kokoshi, informed him that there was a scholarship for him to go to the high school in Manastir. He went there in the fall of 1925. After he got his high school diploma there in 1927, with good results, for the school year 1927-1928, against his wishes, he was enrolled in the Seminary. I finished this school in 1932. In the diploma issued by the directorate on June 18, 1932, it is called “son of Gjergji, merchant”. Looking at the invitations of Migjen at school, one by one, we see all the difficulties he encountered time after time, and the efforts he made to overcome them and move forward. In the final report card of the elementary school in Shkoder, Miloshi has all excellent grades in his studies, and exemplary behavior. Even in the high school of Tivari, he stands high, and only in Serbian he has a “good” grade. In the high school of Manastir, there are the same marks in Serbian, in history and in physics, and “sufficient” in mathematics; Zeal has the grade three. Even in the seminar during the first year, Miloshi only got “good” in Serbian, Greek, Latin and French, but in the second year in all these languages, as well as in Russian, he is “very good”; only in patrology (ecclesiastical literature) there are “good” and “excellent” in pedagogy, methodology, gymnastics and singing.

In the third grade, it drops again to “good” in classical languages and in the main lesson in the Holy Scriptures. He did not pass the grade in Latin even in the fourth grade, but now he is excellent in Russian and very good in Greek; he has a “good” grade in “Dogmatic”, (ie theology), in Psychology and in Logic. In the fifth year, in the last, he is very good in Latin and generally only “good” in the religious studies of the Seminary. What stands out is that as a second grade student, “excellent” in pedagogy and methodical, he only gets the grade “good” in these lessons after three years! – What would have been the cause of these dance fluctuations? – Grades are not always the thermometer of the student’s mental ability. They are often a reflection of the sympathy and antipathy of the professors towards the student and directly show the mentality of the educators. From what his friends say, Miloš has been very correct with his professors, but we believe that it is interesting to note here that once the language professor made this comment in class on a draft of Miloš: “Submission 5; inside 0!” Based on Miloš’s notes in his journals and in his books and hymns, we find that he attached great importance to the French and Russian languages, with which he directly read the most difficult authors from the Confessions of St. Augustine to Dostoevsky’s Karamazov brothers.

On June 18, 1932. The Orthodox Seminary of Saint John the Theologian in Bitolje (Monastery), with public rights, issued Milosh Gjergj Nikolle, after he took the theological exams of maturity from 1 to 17 June 1932, maturity sheet, with 6 grades. good”, 14 “very good” and 2 “excellent” – and declared him a candidate capable for church services, for teaching religion and for higher intellectual studies in university faculties. The time that Miloshi went to the theological high school in Manaster makes a special chapter in his very interesting life; but it will become known to Albanian readers when his living friends will be interested in writing their memories, finding Miloš’s writings, copying his articles in the school magazine and in any other Serbian literary magazine, to reproduce his talks in the class meetings of the club, to collect the letters he sent to his friends and especially the memories of a close circle of students with whom he was associated and together they secretly studied the progressive literature banned at that time . These friends of Migjeni will also show us the authors of classic and modern literature, be it Serbo-Croatian, Russian, French, or other people, that Migjeni read, so that we can once again follow the path that Migjeni walked towards its high social and educational purpose.

Miloshi had a lot of dear friends in the seminar. We ascertain this from their photographs, which each of them sent as a memory, filled with beautiful words of friendship and gratitude, signed by their hand. Among those who are alive, there are also those who will say their word for the friend who died. From this time in Bitolje we know for sure that Milloshi, who felt a deep love for his homeland, was written Albanian in that school, knew the Albanian language then “as every educated Shkodran knows” (to use the expression of a roommate from Tirana at that time in Bitolje), removed Albanian; and the group of Albanian students among whom Milloshi had close friends Jordan Misje, Mirko Nikollen and Zaharia Kadiq and Pandi Papanastasi from Pogradeci, knew him for his moral exponent.

An Albanian student of this school, Theofan Popa, writes about our unforgettable poet: “Ever since I was in high school, when I was still small, I sympathized with Miloš’s beautiful and smiling face. This opportunity came from the caresses he gave me when I was little. Later, I began to sing more often in the choir, because Milosi had a sweet and lyrical voice, and I sang as a second tenor in the choir I had the chance to talk with him more often, understand him better and appreciate him more.  Miloshi stood out as one of the most talented and serious students of our school. He was characterized by a subtle and perfect intelligence. In all meetings and literary conferences of the Seminar, he stood out as a powerful and rich talent. He was not only interested in theology, where he stood out as one of the strongest students, but also art, literature, music and especially social problems. Whenever there was an opportunity for the defense of justice, in whatever country it was, Miloshi erupted like volcanic lava with his fiery and soulful expressions.

Miloshi stood out as one of the most talented and serious students of our school. He was characterized by a subtle and perfect intelligence. In all meetings and literary conferences of the Seminar, he stood out as a powerful and rich talent. He was not only interested in theology, where he stood out as one of the strongest students, but also art, literature, music and especially social problems. Whenever there was an opportunity for the defense of justice, in whatever country it was, Miloshi erupted like volcanic lava with his fiery and soulful expressions.

I often remember when he spoke at conferences. He looks like a flame that burns for human rights. What made Miloš sympathize and be appreciated by all his friends was not only his powerful and brilliant talent, but also his wise behavior in ordinary and special occasions. Miloshi, you don’t deal with small, unimportant things. And he especially hated arguments and pointless quarrels for the moment. When you saw something like that happening among your friends, you blush, get angry and leave alone. It is true that there were often moments of loneliness. Being noble in spirit, he hated brutality and expressed this on many occasions, chastising those friends who behaved badly. In the big hall of our school, during the holidays, balls were organized by high school students. These balls were the joy of the students. Of course, Miloshi also took part in them. His behavior was always measured and with a natural elegance. When he was with the girls, he himself looked like a girl among them, because when he spoke, he blushed more than them. In these cases, it was well understood that he highly valued the female sex.

He saw something higher and more noble in the woman than in the man. Milosh’s lofty and artistic spirit is reflected in his external appearance. The purity, symmetry and simplicity of his clothing made it clear that you were dealing with an elegant soul. One summer, the boarders of the school took them to the Vrajčin Monastery, between the giant cliffs of Peristeri and Lake Prespes. In this picturesque place, with forests, streams and lakes, I had the pleasure of spending more time with Miloš. Kanga accompanied us more. He often sang together with all his friends; but sometimes he and I, he as the first tenor, and me as the second. We sing in Albanian, Serbian, Russian, often under the rays of the sun in the middle of that attractive nature. Of the Albanian ones, he loved kangen the most: “Nen hie t henes rije”. When he sang, he felt great joy. But he really liked the parts of church music. In general, kanga was relaxation for him, he found it a great spiritual satisfaction.

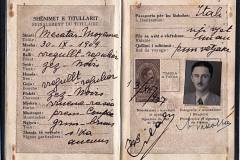

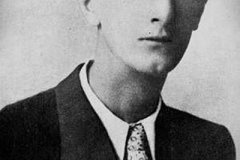

In 1935 or 36, I don’t remember well, I met Miloš in Shkoder; we talked for a couple of long hours. I was surprised by the big changes that took place in his worldview. I remembered him as one of the best theologians, although since then he was too liberal in theology. He reasoned very well when it was a matter of defending the basic principles of Christianity, but regarding the second and third problems in the church, he criticized the rules. But when we met for the last time in Shkoder, he spoke very harshly against the church’s point of view, criticizing the educational spirit of our school. When I reminded him of one of the most righteous professors of the school, he told me: “A Christ on the cross and he are true Christians.” This was my last conversation with Miloš. A few years later, when I returned from Athens after my studies, I heard about a young Albanian poet named Migjeni. I even read some of his poems, but I didn’t know that this Migjeni was our Milosh. When I found out, I was very interested in his entire work, and later “Vargjet e Lira” were published, I bought them and keep them with great love and longing. Miloš stands before me as a hero of morality and justice, and as such he will be unforgettable in my memory and in my heart. With his graduation certificate in his pocket, Miloshi left on June 22, 1932 from Manastir to Tivar, to his sister, Lenka. In the passport that he received in Manastir from the Albanian consulate, we read the holder’s notes: “Tall height, regular forehead, chestnut eyes, regular nose, normal mouth, chestnut hair, shaved beard and moustache, white color, signs of there is nothing special”. After this external description of Miloš, we give this biographical sketch from sister Olga, published in “Pioneri” February 4, 1956. My brother Miloš enjoyed reading his tastes. He always spent his free time with a book in hand. Miloš also liked sports. He knew how to swim very well. He learned swimming in the sea of Tivari, where he spent two years with our older sister, Lenka, where he attended high school. In Shkoder, when he came for summer vacations, he used to go with me to Mesi bridge and to Shiroke, to bathe. Milli spent some vacations in Prespe, where the interns of the theological seminary in Bitol were sent; he used to come here because he could swim, because he really liked nature.

Another sport that Miloshi was involved in was football. He started this game in Bitol, and when he came to Shkoder, he went with his friends to play at Zalli i Kiri. Miloshi has always been delicate in terms of health; we sisters, for fear of being killed in these games, scolded him every time he played. When he was injured, a young cousin, in whose house we lived, tied his wound. When the cousin and Miloshi laughed loudly, we understood that something had happened and the scolding started again… But he laughed lightly and answered us… “any… there’s nothing”. Miloš especially liked music. He played the mandolin. He always sang at home. His favorite song was “Vječerni zvon” (The sound of the night). He sang this in Russian and asked us to join him as well. He sometimes sang “Shubert’s Serenade”. He felt great joy when he heard choral songs. He admired the Russian choir and expressed his opinion about the feelings that resembled him. He had a good ear for music and a very beautiful voice…. Often when we were sad, we begged him to sing for us. Miloš attended many cinemas, the only cultural institution in Albania at that time. He commented on the film a lot, explaining it to the end.

He knew the directors and artists and judged the film from their names. Among the artists he loved Carli Caplin, Greta Garbo and Jeanette Mac Donald. Miloš knew how to play chess well. In the game, he was always calm, with gas on his lips, and whistled some song. He did not drink alcohol or smoke. When he was young, at school, he was at the head of associations organized against smoking. Miloš was loved and appreciated by his friends. In every cultural society at school, or during the summer holidays in Shkoder, the friends chose the secretary. Among his dearest Albanian friends were Jordan Misja and Peko Kadiqi, whom he has in many photographs. From Podgorica, the same uncle who had given him a scholarship to the seminary, is now trying, perhaps without asking his nephew at all, to provide him with a scholarship to the Theological Faculty of Oxford with the help of the Albanian Autocephalous Church, although he knew that before that Miloš did not want to become a priest. We know Miloš’s attitude for sure from his relatives.

Miloshi, on the other hand, after spending the summer, autumn and almost the first month of winter with his sister in Tivar, returned on December 24 to Shkoder to his second sister, Jovanka Perja, with the aim of he was looking for a scholarship or job from the Albanian state. Although he had always been delicate, he seemed in good health this weather and did not show even the slightest sign of illness or weakness.

Miloš had not seen Shkodër for almost ten years, but not only for this cause of the long exile from the country to the east, it would seem like this city is foreign… At first, he stayed locked up at home, or went to visit his relatives and friends, and did not mix with strangers very quickly. Later he got to know local teachers and professors who taught at the state high school in Shkoder. He stole everyone’s hearts with his wise and noble behavior. Thus, while he was waiting for a scholarship to continue his studies at a faculty of literature, the Inspectorate of Education in Shkoder informed him with letter No. 59/15 dated 26/IV/1933, by order of the Ministry of Education No. 115/V dated 23/IV/1933, he was appointed deputy headmaster at the school in Vrake. On May 16, 1933, he was definitively appointed a teacher in this village with a monthly salary of 160 (one hundred and sixty) gold francs.

On May 26, the director of the “Skanderbeg” school verifies that the new teacher started working on April 27. With letter No. 284/191, the Ministry of Education sent to the Prime Minister the biography of Milosh Nikolla that the directorate of the “Skanderbeg” school had posted with No. 21/38 of 23VII/1933. As we know, in the spring of this year, all schools in Albania were nationalized, both for minorities and foreigners, such as clerical ones or those under the control of the church. Vraka is a village a couple of hours away from Shkodra, and it consisted of eighty Slavic farming families, poor and exploited to the point of poverty; these families have been coming here for a long time, they still keep their language, customs and costumes, as well as the school, in which lessons were given in the Serbian language. The Ministry sent Miloš to a nationalized school to teach him now in the Albanian language. When it was Miloš’s turn to be appointed, the consulate of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in Shkoder tried once again to change his mind and advised him to go to Yugoslavia, where he could serve as priest in Banat or study theology in Belgrade. Mirepo Milloshi answered with the language of a patriot, saying that, as an Albanian, he wanted to be at the service of his country and his people. That’s how they recorded her in the “black book” of the consulate, and that of the younger sister Olga Nikolles, who was studying in Sarajevo, in the last class of the Real High School for Girls, they cut her scholarship two months before graduation, without giving her any explanation. In this attitude, in the patriotic attitude of Miloš in relation to the Albanian school, we find the reason why the consul Bozheviqi, his secretary Nikoliqi, someone from his tribe who sympathized with those, as Orthodox, or indeed of Montenegrin origin, ex – the teachers of the Serbian school, the clerics fired by the consulate, and, on top of that, the Catholic clergy opposed to the nationalized Albanian school, the fanatical inhabitants of the city and the countryside – all these remnants of the Middle Ages are leaving for the infamous crusade against the teachers new to the Albanian language, Milosh Gjergj Nikolla.

They went so far in their wickedness as to slander that Miloš had one day removed from the wall the icon of Saint Sava, the protector of Serbian schools, and had stepped on the face of the students! In truth, at first the residents of Vrake, inflamed by the enemies of the nationalized school, received the new teacher very badly, as an enemy of theirs, and brought them to the In truth, in the beginning, the residents of Vrake, inflamed by the enemies of the nationalized school, received the new teacher very badly, as one of their enemies, and brought him all kinds of trouble in every case: they stopped the students from coming to class, they did their best not to supply the classes with wood in winter, so that they would not satisfy his needs in any way, and would not fill any of his deficiencies. Since they didn’t even give him room to sleep in the village, Miloshi was forced to leave as early as dawn, on a bicycle rented from the city, and return home to Shkoder in the evening, thus making a round trip of 14 km. per day.

The double fatigue, the excessive work for school and classes, the lack of enough food and unsuitable clothes for winter, the harsh winds of the Northern Highlands that beat him ceaselessly on his forced journey, the salary that, according to custom, started to be paid after five months – these and so many other daily problems, all together, point to the unhealed wound. In the face of these difficulties, Milloshi continued his work with zeal and love for the poor and oppressed villagers, dreaming of a better future for them, helping them with all his strength to rise from the darkness. of misery. He began to approach the villagers with sympathy and to see their problems.

And slowly they begin to understand that their new teacher is a kind-hearted and righteous man, and they love and honor him with all their heart. Now those farmers, who had looked at him with a bad eye, not only gave him the best housing, and invited him to celebrations and occasions of joy, but they were also angry when his loved ones came from Shkodra, if he did not send them to visit Well, when he was a teacher in Vrake, Miloshi, during a heavy rain, he got wet; it was made into porridge and it was crushed. After some time, one day he came home worried and said to the nanny: “I’m sick, I’m very sick, I’m bleeding! Keep the children away from me. Don’t put me in a container with the others.” In Shkoder, among the young people who were enthusiastically associated with Miloš, besides Jordan Misje, who had been a school friend in Manastir, there were also two others: the consul’s son Bozheviqi and Vojo Kushi. These two were inseparable in Miloš. One day, the consul’s son came secretly to Miloš’s house and said: “My father ordered me not to sell or talk to you, but I love you like a brother. I’m sorry!” And when they walked on the road, in the opposite direction, the Serbian boy looked at him out of the corner of his eye and lowered his head in shame, Miloš looked at him too, and put his lip in the discolored gas. In Vrake, Milloshi came into contact with our villagers for the first time and recognized the causes of their misery; especially their poverty, ignorance and fanaticism left deep traces in his heart. Shocked by this deplorable state, he reflected his experiences in his earliest writings.

These writings are his first letter “Greetings from the village” and the first sketch “Alternative – Sokrat i Vuejtun apo derr i kenaqun”, both published in “Illyria”, on May 27, 1934, – one signed with the monogram M ., and the other with the nickname Migjeni. On June 10, 1934, “Ose…or” was published, and his first well-known poem, “Spirtnat Shtegtare”, in this magazine, on June 17. On July 1, 1934, the sketch: Tragedy or Comedy?” was published, and on July 15 of the same year, the prose story “A chorus of my town”, which ends with a verse fragment. With Migjen, it was seen that in the sky of Albania , where the literary stars seemed to have gone out, a sun was rising. The youth, all the youth, whose hearts cried for a little light and warmth in that cold season of Albanian letters, embraced it with joy and great hopes for the future. of our culture. The clerical press was waiting in a hostile attitude.

The regime’s press tried to make Migjeni their own. Ernest Koliqi, who once recognized Migjeni’s talent, wrote to the editor of Illyris to ensure his cooperation at all costs. of Migjen. The editor-in-chief of “Illyria” magazine sent him this letter, on 4/XI/1935: “Dear Mr. Milosh Nikolla, Shkoder, Mr. s’Uaj’s writings, which at once we felt had a depth of feeling to be noted and especially a human sound towards the suffering of the little ones, we are trying to make them laugh as much as possible on the face of the young people. In order to encourage you to continue as diligently as possible in the literary path that you have so seriously pursued, the editorial board of our notebook decided to publish your poems and pieces of prose on the third page. As you know, on the third page there are only authors who, for better or worse, have received some insurance from the public.

We hope that even after the meeting, Mr. Ej, you will cooperate with us as closely as possible in our Let’s Talk, which, among other goals, also has that of supporting young people with values and generous feelings. The decision of the Editorial Board regarding you is a clear proof of this support. We wish you the best of luck for the benefit of Albanian art and literature. Please send us articles as soon as possible so that your name appears on the third page for at least two weeks. As a reward title, the director of the company sent you Fri. 10 (Sunday) by registered mail d. of today”.

Greetings from Albanian, Asim Jakova These first writings of Migjen are of great importance because they immediately reveal the talent of Miloš’s letters and show how carefully he had preserved his knowledge of his native language, even though he had left the eastern city ten years ago, when he was a reed, they also show the deep and strong feelings he had with his homeland He advised him to stay in a sanatorium. In Slovenia, in Golnik, he made the amount he could with his two scholarships. and requested a visa from the Yugoslav Consulate in Shkodra. Then, on July 23, after finishing school, he received a visa for Greece, as some people who had known life in Greece assured him that with that money he could he spent four months there.

On the 26th we see him in Korçe and tomorrow in Follorin; well, he could not stay in Greece for a month. In Athens, on August 17, he received a visa from the Albanian legate to return to his homeland; and on the 18th of that month he landed in Saranda. For the school year 1935-1936, he was transferred to Shkoder, to the “28 November” school. Even then, he asked to exchange his place with some teacher in Puka, according to the advice of some friends, because that mountain mountain would be healthy for his affected chest. In Pukë, the school worked during the summer season, March-November, and he could spend the winter in the city. Although he later regretted this request (that on January 12, 1936 he wrote to a friend in Tirana (Skender Luarasi) to tell the head of primary education not to consider his request for transfer from Shkodra), on February 14, 1936 , by telegraphic order of the Ministry No. 675/V was transferred to Puka.

Here he wrote on June 16, 1937, his last song “Under the flags of melancholy”. In Pukë, Migjeni continued to develop his wider and richer activity as a teacher and as a poet. There he wrote not only a lot, but also the best ones that remain from his strong pen. All this clearly reflects the misery in which the people have fallen. The sufferings of the Albanian people, in this case especially those of the mountain people, made Miloš suffer more than the disease that was ravaging his lungs. “Yes, yes, Luli’s balloons at Vocerr had the teacher hanged the most!” In Shkodër, during the winter holidays, Migjeni did not stop working, did not relax and did not get tired. He wrote the novels: “Student at home”, “Te chelen arkapia”, “The story of one of them”. “A little poem”, “…Our daily bread, sorry today”. “On the other side of the fence, nothing new” (unfinished) and others, which seem to have been lost. He summarized these under the main title: THE NOVELS OF THE NORTH CITY, and with the subtitle “Chorus of the City”, dated 31.XII.1936, in Shkodër. Although they were written in concept, first-hand, and with a pencil, they are masterpieces both in terms of thought and artistic weaving.

Filip Ndocaj, in a note dated July 5, 1956: “Migjeni, as I informed you”, he writes about this time: “I was transferred to Dardhë te Pukës village; in the spring of 1936, I was going to the village where I was going to open the school for the first time, and that’s why I showed up in Puka, at the school directorate, the headmaster of which administered all the elementary schools of the sub-prefecture. I was surprised when I found Miloš at the door of the school. He greeted me with that optimistic smile of his that made you want to open your heart to him, and it was good for him when he heard that I was transferred to that sub-prefecture. “It’s good that they also sent you to school during the winter holidays, you will be able to attend the university with your own means during the winter, and then take exams…”.

We talked for a long time about our desire to continue literary studies and he advised me to start writing. He gave me this advice the next day. We were walking in front of the school, it was early in the morning, and among other things he said to me: “Why don’t you write?” I knew how strongly he encouraged his friends to write, how wherever he found someone inclined towards the art of letters, he began to influence the necessary subject matter, to direct him towards the sound realism of the critical view of current life, of man. of the day and of the countless issues that this life presented. But I didn’t have confidence in myself: “What about me, how do I know how to write?” I have to learn once and for all…who knows!” But he cut me short: “We don’t need worldly masterpieces, we need writers who know how to reflect the reality they live, who see life without curtains, without incense, without fear. If they don’t know the stylistics well or make verse, grammar, or spelling mistakes… it doesn’t spoil the job.

Stylists will be born later, from here with effort”. He spoke with confidence and his confidence was self-evident. Yes, I had rune, we heard that he also advised others like this, young people who had finished high school and who gathered around him that with his friend they know more, go deeper into culture: he opened new horizons for them, gave them directions in reading theirs, he encouraged them to prepare the real culture, that culture that the school had not given them and that they had to learn by themselves, you read. Miloš’s goal was to have a secular, free, progressive press in Shkodra, with such a dense religious culture, in a country where the press was their monopoly.

In Pukë, the harsh climate aggravated Migjeni’s illness, so he decided to take care of his health; to go out for healing. On December 13, 1937, Milloshi received his permit and visa, on the 20th he left Shkodra and on the 21st from Durrës for Italy; on December 22 in the morning he arrived in Bari and within that day in Turin. It was first settled in Via della Rocca 10, where sister Olda Nikolla lived, who attended the Faculty of Exact Sciences, physics-mathematics branch, at the University of Turin. In the newspaper “Zeri i Populli”, on February 5, 1956, the day the remains of the poet were brought from Italy, we read these memories from the life of Migjen, written by sister Olga Nikolla – Luarasi: In 1932, after finishing the seminary of Bitol, my brother, Miloshi, twenty years old, returned to Shkodër. Although it has always been delicate, this weather looked better than ever. He immediately asked for a scholarship to continue his studies, but he was not given it. Only after ten months, when the schools were nationalized, the teacher was sent to Vrake, 7 km from Shkodra. He had to make the trip to the village day by day by bicycle, in the rain and in the heat, and with the little food he took with him for lunch. When the residents of Vrakas get to know him well, they all begin to love and respect him, but the great hardships he took in the first months woke up his lung disease.

All the efforts to cut him off by transferring him from a malarious village in Shkodër to a mountainous place like Puka, where he served in 1937 and 1937, were of no use. In the summer of 1935, the doctors of Tirana advised him to stay in a sanatorium. They didn’t give him a passport for Golnik, and in Athens, due to lack of finances, he only stayed for one month. On December 22, 1937, he came to Turin. He wanted to enroll in the Faculty of Literature there, and to take care of his health. Since the school documents were returned to him from Tirana as illegal, he could not register. But this evil did not preoccupy him as much as the other one. In the strong climate of Turin, his illness took off. The city doctors advised him to stay in a sanatorium. They put him in the “San Luigji” sanatorium near Turin. Here, at first, it seemed like he was getting better. Everyone told him this: even he himself seemed to feel the improvement. When his friends visited him on Sundays, he was happy and looked forward to them. But this improvement did not last long: he started to feel bad again. The doctors proposed a small operation. Miloshi agreed and the operation was performed in June. The effect of this operation was fatal: his appetite was cut, he lost his strength and his attractive mood. He believed that if I transferred you to a mountain sanatorium, you would get better. We barely secured a place for him in “Ospedale Valdese”, in Tore Peliçe, near Turin, where we accompanied him on August 12. Miloš liked this place very much and said that he would go out and sell it as soon as he rested from the trip. But he never sold it…For two days he was able to go out a little in the sanatorium garden; to dissolve, there was a strong crisis, so much that he required oxygen. For the next two weeks, he sat in bed without moving, with little or no food, talking over and over, completely aware of what was happening to him…”.

His friends were not around at that time, except for his sister, to whom he was careful not to appear so as not to add to his bitterness. He had a great desire to open his heart to someone, because he always asked which of the Albanian students had stayed in Turin during the summer holidays… Then he completely closed in on himself and with a strange resignation waited for the fateful moment, the night August 26, 1938, when he appeared as if in a dream. In Tore Peliçe’s press, we read the obituary (in Italian): “At the Valdes hospital, the Albanian boy who was hospitalized a short time ago, Millosh Nikolla, aged 27, died last Friday. The funeral service, under the leadership of pastor Sig. Giulio Tron, was performed on Saturday afternoon. Of Sister Sig. Olga, who with love and longing stayed by her side in the last and fatal moment, we express our condolences”. In response to these condolences, we also read in those notebooks: “Sister Olga and the Albanian colony of Turin, deeply touched by the unforgettable honor that was paid to the venerable Milosh Nikola, we sincerely thank the director of the Valdes Hospital, the pastor Mr. Giulio Tron, the director and the ladies of “Ville Elisa”, all those who participated in the burial of the beloved deceased”.

What beautiful dream did he have in that last moment when he fell asleep? We owe our life to nature; who has properly used this most precious human capital, has no reason to fear death; let it come when it comes. It is good to love the country and the people with as much love as Migjeni, to have set a high goal for yourself, and as soon as you have started the work, you should notice how death is waiting for you at every step from the beginning of your path. , and reach you far from the clay from which you are cooked and that seems sweeter than honey, far from loved ones who love you, who know your heart and know your mind, far from the heart, – in such a world there is no heart brave enough not to hate the dead and not to cry out with all your heart: “Just don’t let us and strangers die!” And hasn’t this great misfortune found the majority of the Albanian patriots of the Renaissance, from Naum Veqilarxhi and Naim Frasheri to Filip Shiroka and Cajupi? The Mjeda river! “…Oh, father-herna from the harness, one of these unfortunate hearts explained to me. You took my father to your homeland, and your death, From the welding, I am now beating”. Neither the Ministry of Education in Tirana, nor the Albanian Consulate in Turin were at all worried about the bad health condition of the teacher Millosh Gjergj Nikolla. A student who returned from Turin to Albania for the summer holidays wrote to Migje’s sister: “We wrote if anything was done to go to Miloshi in Robiland. Get rid of the consul and consocios every day, otherwise you won’t be able to finish the job”. The Chief Consul in Turin did not consider it worth even informing his Ministry of the death of Miggen.

But the news of the death of the young Albanian poet, after all, caused deep sadness throughout Albania. Naturally, those who took care of the first mandate were the poet’s relatives. The black news, by letter, arrived in Shkoder on August 30. Jovanka’s answer to her sister Olga, in Turin, sounds like a howl, like a cry, that pierces your heart. From Shkodra, since the first days of September, the gjema reached Tirana, and from there to Korça, Berat, Lushnje and even the farthest villages in the South. The common pain made all the poet’s lovers feel that they were of the same tribe and of the same blood as him. Many, many Albanians addressed the family with comforting words. Most of the letters are from young Albanians and almost all of them have this content: “With him, not only you have lost a dear brother and a dear friend, but also our country a very valuable person”. “Ah desert hermit, how rare you are! Where did he wash my bones and close me in his own way in the black soil…Olga dear, how hard it is for you; Do you have any restaurants nearby?” – they sent a woman from Shkodra to Migje’s sister; and another Albanian woman who met him on September 15, 1938 from Salem, New York in the United States: “It is with great sadness that we hear of the death of your only brother. It would be better, Olga, if we hadn’t met at all, because it made us very sad!”

Even the official press in Albania did not pass this great loss in silence. In addition to the magazines “Albanian Effort” and “Kombi”, in which some of Migjen’s novels and poems were published, his death was also mentioned as a serious loss by the Ministry of Education’s “Pedagogical Magazine”, which noted only the great qualities of the teacher. The clerical press spent Migjeni’s death in complete silence.  The many telegrams and letters that the sister received from the Italians, who had known Miloš and had become friends with him, were a relief of grief for the unconsoled sister, in whose arms Migjeni closed her eyes forever. With the help of the press, Migjen’s family expressed their gratitude to their Italian friends for the comforting words, and to the Municipality of Torre Pelliçe for the beautiful place they assigned in the city cemetery for the corpse of our beloved poet, and later also for the great care that showed 18 consecutive years of keeping that grave, until the Albanian government brought his remains to bury them in the land where Milloshi was born, on 5.II.1956.

The many telegrams and letters that the sister received from the Italians, who had known Miloš and had become friends with him, were a relief of grief for the unconsoled sister, in whose arms Migjeni closed her eyes forever. With the help of the press, Migjen’s family expressed their gratitude to their Italian friends for the comforting words, and to the Municipality of Torre Pelliçe for the beautiful place they assigned in the city cemetery for the corpse of our beloved poet, and later also for the great care that showed 18 consecutive years of keeping that grave, until the Albanian government brought his remains to bury them in the land where Milloshi was born, on 5.II.1956.

Published for the first time on Facebook – Albanian Cinematography: October 2019.

__________

Albanian Cinematography in activity since 2013

Reference: “MIGJENI – LIFE AND WORK”

Follow us: Blog: https://albaniancinematography.blogspot.com/ Vimeo: Albanian Cinematography (vimeo.com) Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ksh.faqjazyrtare Dailymotion: https://www.dailymotion.com/kinetografiashqiptareartisporti YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCDRYQ5xCyGkfELm3mX8Rhtw

Discover more from Albanian Cinematography - Sport

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.